This unit will be a part of the year long emphasis on poetry. Because my eighth graders have responded so positively to poetry study in the past, and because I believe that the study of poetry provides a strong foundation for the study of other literary forms, I hope to find time for poetry study each week during the school year. This unit is appropriate for all three situations.

In addition, I plan to start an after school poetry club next year. I teach both an eighth grade regular Communications class (our terminology for language arts) and an eighth grade Creative Writing class.

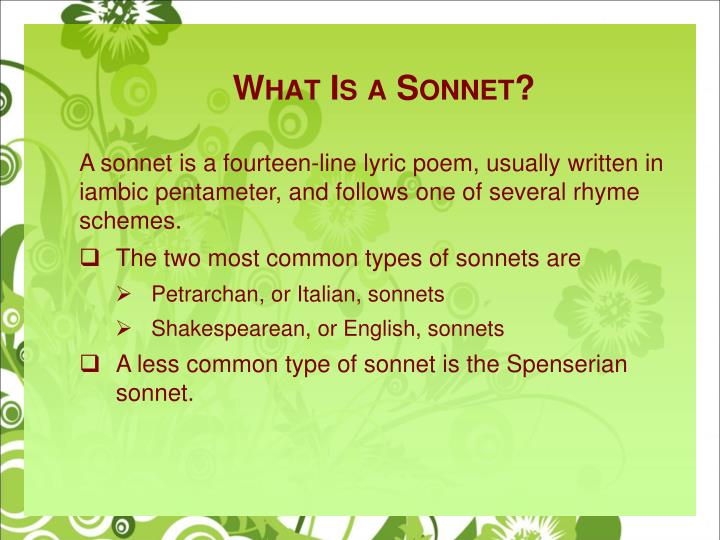

However, most of what is presented is appropriate for other middle school grades as well as for high school. I teach eighth graders in an urban middle school, and so had my own students in mind when creating this unit. The decision to write this unit stemmed from an awareness that many middle school students lack experience in both of these areas. The second objective is to create a framework that enables students to experience success in the close reading of poetry. The first objective is to introduce the concept of form in poetry and its importance to the poem's overall impact. Dedicated to Sir Walter Raleigh and loosely based on Spenser’s visit to London in 1591, the poem is, like The Faerie Queene, an allegorical work, with Spenser (who appears in autobiographical form as Colin Clout himself) making many anonymous references to his fellow poets of the Elizabethan age.Studying the Sonnet: An Introduction to the Importance of Form in Poetry by Lynn Marsico OverviewĪlthough this curriculum unit will focus on the sonnet and its history from Petrarch to contemporary times, two core objectives have guided its development. The critic Alastair Fowler has called it the ‘greatest pastoral eclogue in the English language’. One of Spenser’s pastoral poems, this one was published in 1595, the same year as Amoretti. That us late dead, hast made again alive … Sith thou are come, their Cause of Merriment, The Fields with faded Flowers did seem to mourn,Īnd all their Flocks from feeding to refrain Īnd all their Fish with Languor did lament:īut now both Woods, and Fields, and Floods revise,

#Spenserian sonnet examples by students full#

The Woods were heard to wail full many a Sythe,Īnd all their Birds with Silence to complain Whilst thou west hence, all dead in Dole did lie Hast made us all so blessed and so blythe. Was heard to sound, as she was wont, on high, That sith thy Muse first since thy turning back Had all the Shepherds Nation by thy lack?Īnd I, poor Swain, of many, greatest Cross: But there’s a twist (and a turn, or a volta, as in most sonnets): here we have another take on the popular Renaissance conceit that the poet’s sonnet will immortalise his beloved.Ĭolin, my Life! my Life! how great a Loss He wrote his beloved’s name out a second time, but again the tide came in and obliterated it, as if deliberately targeting the poet’s efforts (‘pains’) with its destructive waves.

Spenser tells us that he wrote his beloved’s name on the beach one day, but the waves came in and washed the name away.

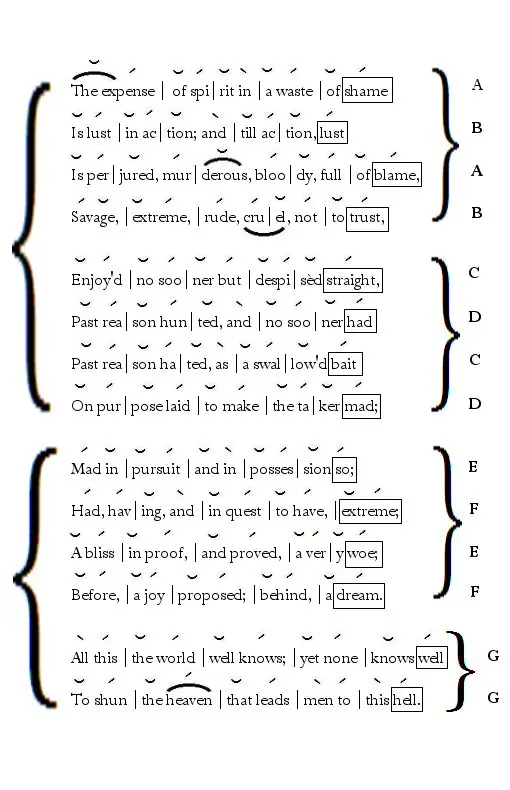

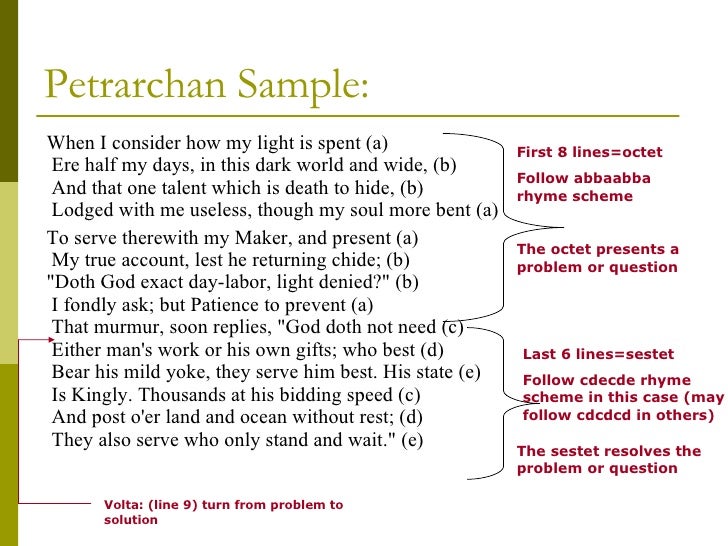

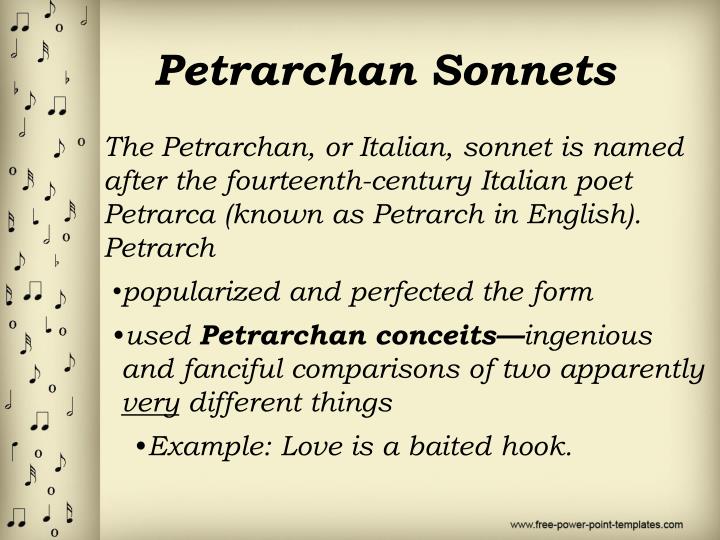

Even when using these established forms – and the sonnet had been in England for half a century when Spenser wrote his – he saw fit to innovate with it. The best-known poem from Spenser’s 1595 sonnet sequence Amoretti, which he wrote for his second wife Elizabeth Boyle (of whom more below), this one is rhymed ababbcbccdcdee, making this a Spenserian sonnet, a sort of halfway house between the original Italian or Petrarchan sonnet, with its octave and sestet, and the English or Shakespearean sonnet, which also ends with a rhyming couplet, as Spenser’s does.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)